|

A

NEW CAUTION: Macon's roadbusters

Familiar

fight:

Middle

Georgia road-builders, many residents are locked in

struggle over growth.

Dan

Chapman - Staff - www.AJC.com

Monday,

May 8, 2000

Macon ---

The hairdresser feared her mostly rural community would

turn into an industrial park.

The college

administrator suspected neighborhood streets might be

five-laned.

The

housewife envisioned a bulldozer toppling the towering

magnolia where her children play.

"What we all

have in common," says Suzan Rivers, the housewife, "is a

love of this city. We don't want it to get torn up."

They ---

housewives, teachers, retirees, preachers, architects,

dentists, lawyers, foresters, doctors --- also didn't

want this midsize central Georgia city to turn into

another traffic- and sprawl-fueled Atlanta. So they

banded together to fight City Hall, transportation

officials and the road-builders who are spending $320

million paving miles of Bibb County.

"Why can't

Macon learn from Atlanta's mistakes?" asks Lee Martin, a

small businessman whose 1960s idealism was rekindled by

the road-building battles.

Martin,

Rivers and dozens of other activists decided Atlanta's

history is, indeed, replete with sprawl-busting lessons.

Their education can be summed up in a word: CAUTION.

Citizens

Against Unnecessary Thoroughfares in Old Neighborhoods

--- CAUTION Inc. --- was formed in 1982 to combat plans

to build a highway from downtown Atlanta east toward

Stone Mountain. If built, neighborhoods like Druid Hills

and Candler Park would have been ripped apart.

For 20

years, it was a citizens-vs.-developers battle played

out in courtrooms, jail cells, kudzu-filled fields and

politicians' chambers. More than 500 homes and untold

acres of land were leveled.

In the end,

though, CAUTION prevailed. Today, the Freedom Parkway

meanders 3.1 miles from the Downtown Connector, past

Jimmy Carter's presidential library and public-policy

center, before dead-ending at one of Atlanta's most

cherished parks.

CAUTION

Macon fights strikingly similar --- and, at times, nasty

--- battles. Name-calling. Lawsuits. Allegations of

wasteful spending, political chicanery, conflicts of

interest.

Dan Fischer,

a former urban planner and city administrator in

Colorado, accuses city, county and state officials of

not fully informing Bibb County residents of the

magnitude of the road-building projects.

"My

experience in local government didn't prepare me for

Macon government," says Fischer, now an administrator at

Mercer University. "It's when they started doing

obviously unjustified damage to neighborhoods that

people realized there was something illogical about the

process. They were willing to sacrifice the integrity of

in-lying neighborhoods strictly to accommodate suburban

sprawl."

Hogwash,

responds Larry Justice, the longtime Bibb County

commissioner who calls CAUTION "an outside group of

agitators."

"Here's

where I have a problem with these CAUTION people: They

do not want growth," says Justice, a commissioner for 28

years. "They're being shortsighted. They're not looking

down the road for their children and their

grandchildren."

CAUTION has

won and lost road-building battles during its two-year

fight. Its most recent defeat came in February, when a

federal judge dismissed CAUTION's lawsuit to keep a

two-lane road from turning into a five-lane

thoroughfare. Yet even its critics agree CAUTION has

changed the democratic dynamic in once-placid Bibb

County.

'We

want to catch up'

Robert

Fountain gleans different lessons from Atlanta's

history. As Bibb County engineer, Fountain ascribes to

the grow-or-die theory of economic development. Good

roads attract business. New business keeps property

taxes down. Lower taxes equal happier citizens.

"Ideally, I

see us as a second hub to Atlanta in economic growth,"

says Fountain, county engineer for 26 years. "We want to

catch up. Since the '40s, we haven't spent any money on

this town. This is the best thing to happen to this

whole community."

Fountain and

others envision the transformation of this old mill town

into a distribution hub with rail lines and four-lane

roads heading in all compass directions. One of the

keys, Fountain and others say, is to improve and expand

the roads leading to the Perimeter-like beltway.

The Fall

Line Freeway would serve as one leg of the

triangle-shaped outer belt. Planned as a 215-mile

highway linking Augusta with Columbus through Middle

Georgia, the stretch around Macon remains in limbo. The

road-bulders' preferred route runs through

environmentally sensitive wetlands and near the Ocmulgee

National Monument and burial grounds.

State and

local transportation officials say their route wouldn't

unnecessarily damage the 20,700 acres of "cultural

property" considered historically important to the

Muscogee Indian Nation. They're submitting an

environmental assessment to the feds this month for

approval.

Roughly a

third of the $320 million in state, federal and local

road-building money would help finish the Fall Line

Freeway. While many a CAUTION member individually

opposes the road's local segment, the group hasn't taken

an official position.

Macon, whose

air grows increasingly polluted each year, is expected

to achieve this summer the same dubious air-quality

non-attainment distinction that Atlanta already owns. If

so, future road-building projects --- and Bibb County's

hoped-for growth --- may be slowed.

Yet Macon

barely grows now. With 115,000 citizens, it averages

less than 1 percent growth per year. Fountain says the

region averages maybe 6 percent growth.

But critics

consider that insufficient to justify 62 road projects.

"All they're

doing is taking federal money and just laying down

asphalt without rhyme or reason," says CAUTION's Tom

Scholl, an ordained minister. "We want every dime of the

money spent. We just don't want them to spend it where

they want to spend it."

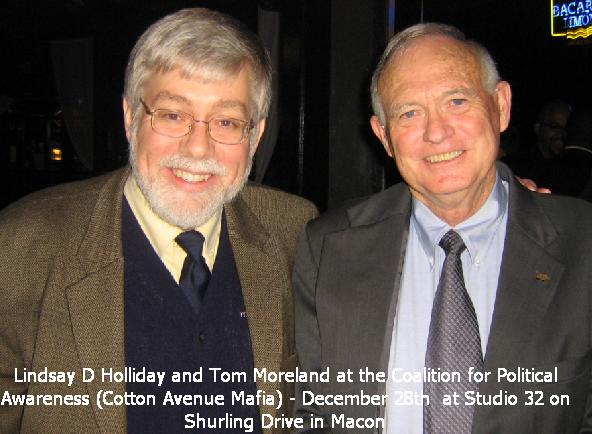

"Pennies for

Progress" is how Macon and Bibb County officials ---

with a healthy assist from Atlantan Tom Moreland's

engineering and program management firm --- campaigned

for their road-building referendum in 1994. With an

additional plea for Macon's future economic viability,

the 1 percent sales tax proposal garnered a slim

majority of Bibb County voters.

More than

$130 million has since been raised locally.

Grass-roots

effort

Graders and

dump trucks crisscrossed Bibb County. Downtown roads

were expanded and repaved. Front yards in intown,

suburban and rural communities were ripped up to make

room for two-, three- and five-lane roads. The goal

remains to ease congestion and make smooth the drive

from city to suburb to country.

By September

1998, the road-building revulsion had crested. CAUTION

Macon was formed, largely with the moral and technical

support of its Atlanta kin --- including Tom Marney, Jim

Chapman and Mary Norwood --- and the financial backing

of more than 1,000 Maconites.

The

grass-roots organization mobilized quickly and

effectively. Core members focused on specific topics.

Scholl, for example, crunches traffic counts and growth

projections. Rivers researches historical precedents.

Susan Hanberry, a middle-school teacher, is the

environmental whiz. The Internet is tapped for

information about road battles across the country, as

well as to keep CAUTION members and journalists informed

(www.cautionmacon.org.).

Neighborhood

associations and politicians were mobilized. In historic

College Hill, neighbors tied hundreds of yellow ribbons

around threatened magnolias. Similar acts of protest

took place in the predominantly black neighborhood

surrounding Jeff Davis/ Telfair Street.

CAUTION

railed against poor planning, in general, and

unfaithfulness to the county's land-use plan, in

particular. The crux of CAUTION's discontent, though,

was a feeling that the integrity of intown neighborhoods

was being compromised to further suburban sprawl and the

industrialization of Bibb County.

Justice, the

chairman of the county commission the last 11 years,

scoffs at CAUTION's assertion, insisting traffic counts

and Macon's development as a regional job,

entertainment, medical and educational hub justifies its

road-building largesse.

"All this

hoopla about sprawl is ridiculous," he says. "We don't

want to see another Atlanta in Macon. But at the same

time, we do want to see good, solid growth."

CAUTION,

further miffed that some projects changed dramatically

post-referendum, was fed up. A show of force was needed.

Roughly

1,000 people showed up for CAUTION's September 1998

kickoff rally in front of Macon's courthouse. Their

grievances were many. But their immediate demands ---

most of which were met --- were few.

They wanted

nationally renowned and environmentally sensitive urban

planner Walter Kulash hired as a consultant. They wanted

finished road projects better landscaped. And they

wanted only elected officials to serve on the

road-building executive committee.

Even state

officials complained of the lack of citizen

participation.

In a

November 1998 letter to Macon's mayor, former state

historic preservation officer Mark Edwards wrote "there

seems to be a lack of meaningful public participation in

the local transportation planning process, at least

concerning impacts to historic properties." Edwards

later accused a top Georgia Department of Natural

Resources official of "making a mockery out of the

democratic process" in his "zeal" to build the Fall Line

Freeway.

Bibb

County's engineer acknowledges that public officials

should've been more considerate of citizens' concerns.

"We had a

lot of (input), but the timing may not have been the

best," Fountain says. "If I could do it all over again,

I would set up a system to bring in neighborhood

(residents) at the very, very beginning of the project."

Unmollified,

CAUTION decided to get tough. They needed a fight. They

found one on Houston Road.

A

crushing blow

Traffic is

light along Houston ("How-stun") Road as a minivan full

of CAUTION members wends through south Macon. They point

out their homes, their churches, the pecan orchards and

cotton fields. They ignore the yellow bulldozers, the

scraped-flat fields and the powerfully sweet smell of

uprooted trees.

CAUTION

latched on to Houston Road as the most egregious of

road-building projects. Prior to the referendum,

residents were told that only a turn lane would be added

to a 3.2-mile stretch of road. Post-referendum, they

learned Houston would become a five-lane thoroughfare.

"Little by

little, it went from two lanes to three lanes to five

lanes," recalls Marilyn Meggs, a

housewife-turned-activist. "They told us it was a done

deal."

CAUTION

filed a lawsuit last October to stop the $8 million

Houston Road project. The group said the Georgia

Department of Transportation failed to adequately

consider the road's environmental impact. Kulash, who

was hired by project manager Moreland Altobelli,

testified against Houston Road, saying it would

encourage strip development.

Kulash's

switch fueled a conflict-of-interest charge lodged by

the road-builders. They also said Kulash designed

projects without a Georgia engineer's license --- even

though he'd worked with them for months.

In February,

a federal judge denied CAUTION's request to halt the

Houston Road project. It was a crushing blow, but not a

fatal one.

CAUTION is

an undeniable force in Macon life. It has forced

road-builders to scale back projects in working-class

west Macon, upscale north Macon and historic downtown

Macon.

Citizens in

neighboring Monroe County now seek CAUTION's advice on

ways to combat road projects. The nonprofit sponsors

"smart growth" forums to gauge candidates' views.

It's

investigating ways to legislatively ensure road-builders

don't steamroll other smallish communities. CAUTION

members know once Macon's fight ends, road-building

battles will continue in other Georgia towns with

growth-at-all-costs politicians and pliant,

unsophisticated citizens.

"This is

little ol' Macon," says Suzan Rivers. "If this is

happening here, it's happening all over Georgia. Think

how many neighborhoods all over Georgia are being

destroyed."

http://www.accessatlanta.com/partners/ajc/epaper/editions/monday/business_93617573249d203910d2.html

|