Levee Problems in Macon, Georgia:

The Army Corps of Engineers is once again (2007); and again (2002), and again (1997), and again (1995 and 1993) pressuring the City of Macon to pay for repairs to a seriously flawed Levee design system ...

| The Macon Levee - - Design Problems: |

||

| Bigger Images:

Floodplain

Detailed illustration

2004. I-16

vs

Levee

protection

of 3000 acres. Geological

size

of

the

unfettered floodplain Proposed

Super-Imposition

of

Eisenhower

Pkwy Extension Who

owns

the

floodplain? Important Information: Army Corp's Section 1135 Grants here. Articles from 1994, 1998, 2007, 2008, 2009, the Great Flood of '94, A Solution to SPLIT the Levee, Critical Flooding Issues, Eisenhower Parkway Extension, Levee Scam plans, Images and Maps: Levee/Flood-Plain.jpg Historic-Floods-Graph.jpg PublicAndPrivateLands3-27-2006.jpg BrickYards and MaconLevees.jpg Shaded - Traditional Cultural Property of the Muscogee-Creek Nation BS-desig-boundary.jpg CherokeeTCP.jpg EPE-proposed.jpg aTCP.jpg Vision of a Great Ocmulgee River National Park Video of a Levee Break 16MB size Windows Media Video here. Removing Levees in LA article (click for Slideshow of 1994 Flood)

|

||

|

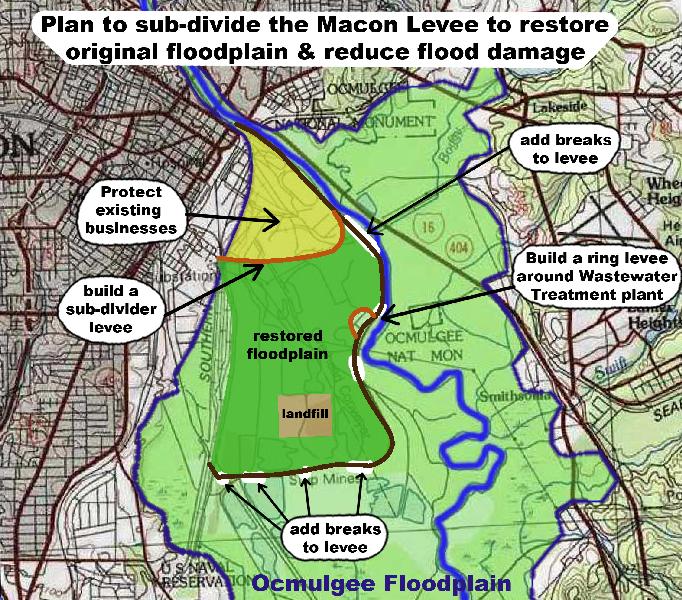

| Best Proposed

Solution: Divide the

Macon Levee |

||

|

||

|

Analysis of Macon Levee Alternatives and Opportunities By John Wilson – revised 2-10-07Ecosystem Restoration The Corps has two continuing authorizations from Congress to address ecosystem restoration. These continuing authority programs allow the Corps to partner with non-federal sponsors to plan, design and construct small ecosystem restoration projects. The first program is the Section 1135 Program, which was authorized by the Water Resources Development Act of 1986. This authority allows the Corps to modify existing Corps projects to restore environmental quality. The Corps can also restore areas outside of Corps project lands that are impacted by a project. The maximum federal cost limitation for Section 1135 projects is $5 million, and the cost-sharing formula is 75 percent federal, 25 percent non-federal. Non-federal partners for these projects may be governmental bodies, or non-profit organizations that are capable of performing operation and maintenance of the Section 1135 project, if needed. The second ecosystem restoration program is the Section 206 Program, which was authorized by the Water Resources Development Act of 1996. This program is limited specifically to aquatic ecosystem restoration, but unlike Section 1135, Section 206 projects may be implemented anywhere with no ties to an existing Corps project required. The Federal cost limitation for these projects is also $5 million; however, the cost-sharing formula is 65 percent federal and 35 percent non-federal. And like Section 1135, non-federal sponsors may be governmental bodies or non-profit organizations capable of performing operation and maintenance. The division currently has 17 Section 206 projects in planning or design stages.

Both the

Section

1135 and Section 206 programs allow credit against

the non-federal

share of costs for the value of lands, easements,

rights-of-way,

relocations and disposal areas, as well as for

work-in-kind. This

helps to ease the cash requirement for non-federal

sponsors. The Corps have focused on the Section 205 Program to certify the Macon Levee as providing 100-year protection to the area behind it. However, Macon would be better served by conducting a Section 1135 Study - Project Modifications for Improvement to the Environment. The upfront costs will be lower and the economic, recreational and environmental results will be higher. There is a possibility that utilizing a combination of projects, programs and existing local government-owned land could eliminate all costs to the City of Macon. Conducting a study for a Section 205 Project has the following problems and Section 1135 offers these solutions:

The Section 1135 Program offers an opportunity to sub-divide the Macon Levee and restore original floodplain, which will lower overall flood levels. Subdividing the levee can afford better protection, maybe 500-year protection, for the existing businesses concentrated behind the upper end of the levee.

However, Section 1135 has the same costs for the study, but only requires the local sponsor to pay 25% of the project cost. If the project costs are the same those for a Section 205 project, then this 10% savings could save Macon up to $350,000. If some of the City’s land behind the Levee, the MWA’s Van Dyke property (300ac.), Bibb County’s 280 acres of wetlands at the Sheriff’s firing range and possibly the 300 acre Scott McCall Archeological Reserve can be incorporated into this project and used as matching funds, then the cash cost of the local share can be further reduced. ( Quoting the Corps - “Both the Section 1135 and Section 206 programs allow credit against the non-federal share of costs for the value of lands, easements, rights-of-way, relocations and disposal areas, as well as for work-in-kind. This helps to ease the cash requirement for non-federal sponsors.”) I don’t know if Section 205 allows this. The MWA’s Poplar St. Wastewater Plant accounts for approximately 60% of the investment behind the Macon Levee and yet the City of Macon is planning to undertake this study and project without their financial support. The Section 1135 Program does allow structural elements such as a ring levee around the treatment plant. The MWA should be a funding participant in whichever project is chosen. The close proximity of the Ocmulgee National Monument and Bond Swamp National Wildlife Refuge will strengthen the case for preserving nearby floodplain and incorporating it into their boundaries. Other federal grants and funding opportunities exist to purchase, preserve and restore floodplain. Georgia’s Land Preservation program could also be used to help acquire floodplain lands, especially since there would be substantial local and federal financial participation and the wetland, floodplain, tourism and recreational values of these lands are so significant.

If Macon pursues a Section 205 project, Macon will transform its faulty levee into a good levee. However, the trees growing along it, which provide shade and beauty may have to be removed. The general public will not see or be able to enjoy any additional benefits from this $1 million plus expenditure. Businesses behind the levee will feel better, but will have only marginally better protection from flooding while upstream and across-stream homes, businesses, parks and highways will continue to be subject to excessive flooding. On the other hand, if a Section 1135 project is undertaken which divides the Macon Levee and restores much of the river’s original floodplain, then flood levels and thus, the chance of flood damage will decrease both behind the levee and up-, down- and across-stream. The floodplain lands and easements purchased for the project can become park lands open for public use. With a $5 million cap on projects, this project could possibly result in the linkage of the Bond Swamp Refuge to the Ocmulgee Monument. Currently, the Macon Levee causes the eastern floodplain to flood more. Restoring portions of the western floodplain will relieve excessive flooding conditions on the eastern floodplain. Funding may be available for purchases on both sides of the river. In conclusion, with a 1135 project handled in a cooperative manner, Macon could end up with lower or no costs, greater flood protection behind the remaining levee, lower flood levels and frequency up and down the river, an expanded park system with greater recreational and tourism opportunities. It could also generate more matching grants, as well as providing momentum for preserving our river system’s heritage and environment and promoting downtown’s development.

First, the Macon Levee had water boil up under it during the last two minor floods. This was not a maintenance deficiency but was due to the sandy soils located beneath the levee. Prior to the building or the Macon Levee, this area had sloughs and old riverbeds through which floodwaters regularly flowed into the eastern floodplain. Evidently, the sloughs filled up with sand and allow water to flow through them during floods. The recent boils occurred adjacent to the 1994 breach in the levee, which was repaired with 100% federal funds under Public Law 84-99. The recent boils appeared during flood events of about 22’ to 25’ as measured at the 5th St. Bridge. Minor floods of this magnitude can be expected to happen every 1 to 5 years. Macon could wait till the next flood that produces boils and then apply for a PL 84-99 project to fix the problem within the 30 day application time period after a flooding event. This type of project is 100% federally funded and this program “provides for a nonstructural alternative to the structural rehabilitation of flood control works damaged in floods.” It can be used “to restore natural flood plains” and “habitat restoration is recognized as being a significant benefit that can be achieved.” This program doesn’t allow major improvements, but is more of a fix it program. This program is an opportunity that needs investigating. Secondly, the Corps of Engineers Reform Act of 2001 (H.R. 1310 and S. 646) have been introduced into both houses of Congress (in 1992 – I don’t know if it passed). This act has many features, which could benefit Macon if the levee question could be put off until it is enacted. Also, if a study is completed, but the project not begun before this law is enacted, the project may not be justified under the new guidelines and requirements. Part of the act states that Corps guidelines will be revised “to eliminate biases and disincentives for nonstructural flood damage reduction projects” and “to encourage, to the maximum extent practicable, the restoration of aquatic ecosystems.” The Governor of Georgia or the Fish & Wildlife Service or National Park Service can request the appointment of an independent review board to review a Section 205 Macon Levee project. The Act also requires full and immediate wetlands mitigation. The Corps “shall acquire and restore an acre of habitat to replace each acre of habitat negatively impacted by the project” and “shall fully mitigate the adverse hydrologic impacts of projects.” The Corps must also “complete 50 percent of required mitigation before beginning project construction and complete the mitigation before the last day of project construction.” I don’t know exactly how this will play with a Section 205 improvement of the Macon Levee, but it should not hinder a 1135 project. The Corps has said that they could consider the Macon Levee as not existing since it has passed its 50-year life as regards their determination of economic benefits. If this is so, then the environmental impacts should also be based the same premise that the levee does not exist. If this is the case, then the improved levee plan will take the whole western floodplain (3,000 acres) out of the river’s hydrological ecosystem and will increase flood damages on the whole eastern floodplain. This scenario creates a tremendous acreage to be mitigated for and the negative environmental impacts on National Register floodplain wetlands would quite possibly doom the project. Depending on how they do it, the Corps may have to buy a lot of wetlands for mitigation and it could result in a positive overall impact. Currently, they have much less strenuous mitigation requirements.

One of the concerns expressed about subdividing the Macon Levee and restoring flow to the western floodplain is “what about the brick companies?” In 2005, Cherokee Brick Company received a Corps Section 404 Permit to mine 570 acres of floodplain wetlands and to mitigate by preserving, restoring and creating 1260 acres of wetlands inside and downstream of the Macon Levee. They also purchased 576 acres around Lamar Mounds to preserve as wetlands mitigation for their new mining permit. Breaching and sub-dividing the Macon Levee to restore flow through the western floodplain could allow flow through the mitigated wetlands in the western floodplain. Floodwaters routed through the western floodplain need to be able to continue their flow downstream and there is a path of previously mined lakes and wetlands to facilitate this flow. Cherokee is not mining behind the Macon Levee and their operations are moving well south of the Levee. Boral Brick is also mining south of the Macon Levee. Both brick companies have their own levee systems. However, the brick company’s levees do increase flood levels and any Corps studies under any program should require hydrologic modeling to determine their impact and to determine opportunities to minimize flooding. Brick levees should be removed or lowered when mining operations cease in an area. The Section 1135 program will allow for greater study and coordination with the mining operations to minimize flood damages and maximize wetland and floodplain restoration.

The Macon Landfill is located in the Ocmulgee’s floodplain. It is set to close in the near future. Flooding should not affect it any more than it does now, but that is an issue that needs study. Macon has an agreement to use an alternative landfill if flooding prevents access to the Macon Landfill. The Flood of ’94 blocked access to the landfill for only 4 or 5 days. Consultation with the State EPD is needed.

Applying for a Section 205 Study and Project at this time represents a concession and an agreement to pay for deficiencies in the Macon Levee which have been argued over with the Corps in past years. The problem with trees growing on the levee is expected to cost about $1 million to rectify. The Corps says it’s a maintenance problem and Macon should pay to remove them. Macon says some were there when the levee was built and the Corps never mentioned them as a problem before about 1991. Macon wants the trees to stay to maintain the their scenic and shade values for when the Ocmulgee Heritage Trail is extended down the levee in the future. Macon should probably seeks legal assistance in determining the cause, remedies and costs before entering into a study which financially commits Macon to a project which includes these costs if they are not Macon’s fault and responsibility.

The “Takings” issue – from a Corps memo describing a July 10, 1997 meeting with Macon’s Mayor. “There would, however, be some flooding impacts on existing property owners in the now protected area including the wastewater treatment plant. This brought about a discussion of a takings analysis. Such projects being undertaken by the Corps have surfaced new issues whether or not those projects result in a takings of private real property interest for which compensation would be due under the Fifth Amendment of the Constitution. Analysis, such as the one recently done for the Lower Savannah Environmental Restoration Project, are concluding that if the restored flows are less than the historical flows before the project existed there are no takings. Only if we induce new flows higher than pre-project flows, would we be affecting the property owners rights and which may require compensation.” Currently, the Macon Levee does increase up-across-and downstream flooding of private properties. These private landowners can sue the City of Macon for damages every time there is a flood event, which impacts their property. They can sue on the basis of “Trespassing” and “Takings” and “Nuisance.” In the 1980’s, Mr. Putnal sued Boral Bricks for building a levee on the western floodplain, which increased flooding on Putnal’s land on the east side of the floodplain. Both parties hired hydrologists and Mr. Putnal won the case. Boral Brick had to remove the levee and pay damages. In a major flood, Macon could be held liable for major damages. I don’t know why no one sued after the 1994 flood. They may not have understood the dynamics and causes of the excessive flooding or the legalities or maybe insurance and federal programs covered the damages. With this said, another alternative for handling the Macon Levee situation may be for the City to bulldoze 4 or 5 breaks in the levee and use the dirt to build a low sub-divider levee. This may be the most economical plan for the City. It would spur the MWA to build a ring levee for themselves. |

||

|

Solution may be to divide

the Macon levee

By John Wilson Posted on Wed, May. 01, 2002 http://www.macon.com/mld/telegraph/news/editorial/letters/3169009.htm The Army Corps of Engineers is seeking $260,000 to conduct another study of the Macon Levee. Other studies were in 1993, 1995 and 1997. The goal is to certify the levee as providing 100-year flood protection to the 500 acres of semi-developed land and 2,500 acres of undeveloped land located behind it. Taking this area out of the "100-year floodplain" (on paper) and running the proposed Eisenhower Parkway Extension through this "former" floodplain area would promote investment and development behind the levee. Quoting the Corps, "Without this, investors would be more inclined to expand or establish new facilities somewhere else." Maybe that would be wise? Macon/Bibb paid about $360,000 for Corps studies from 1990 to 1996. They never received the Corps 1997 study which was advertised for public comment, but then withdrawn and never released because the Corps' belated economic analysis showed their levee-raising project to be unjustified. The Corps never surveyed the economic damage from the '94 Flood either behind or outside of the levee. They didn't do hydrologic studies to model the '94 Flood to see what impact the levee and its failure had on flood levels. Their 1995 study (p.14) stated that "the levee has never been overtopped" and their 1997 study said, "Since there are no historical damages to use at Macon." The Corps said the Flood of '94 never happened so they could increase the cost/benefits by using standardized, rather than lower actual damages. They used new FEMA guidelines which allowed them to reduce their levee-raising plan by three feet and still certify it as providing 100-year protection (on paper). Still, they couldn't justify raising the levee economically. Now, the Corps says the levee is deteriorating due to trees growing on it and water flowing under it. Yet, a 1997 Corp memo says "The public has presented strong evidence that trees have not been a detriment to the structural integrity of the levee systems in California. And they are winning many cases" A 1998 memo says portions of the Macon Levee are "underlain by exceptionally pervious sands that are very efficient at transmitting hydraulic head" under the levee creating boils and seepage during floods. The Corps even believes the levee would have failed at the breach site in 1994 from water flowing under it even if the levee had not been overtopped. Do we need to dig up and pack clay under the levee now? The point is that no matter how much we do or spend on the levee, we can't stop the river from reclaiming its floodplain some day. We can offer false hope and encourage people to invest their money in the floodplain. We can even bail them out with federal funds when they get flooded, but why? Why strengthen the levee so it will stand while our interstates and and existing businesses and neighborhoods flood, as happened in 1994? The Macon Levee was and is a bad idea. The solution may be to divide the levee, strengthening the upper portion to protect existing development and breaking the lower end to restore the original floodplain, thus reducing flood levels all along the river. The problem is I wouldn't trust the Corps' study of anything. John Wilson is a resident of Macon. http://www.macon.com/mld/telegraph/news/editorial/letters/3169009.htm |

||

| Below

is

a well-researched

MaconTelegraph.com article

from 2004 |

||

| |

Posted

on

Wed,

Jul. 07, 2004 http://www.macon.com/mld/macon/news/local/9094353.htm Officials thinking it's back to the future for Ocmulgee flood plain By S. Heather Duncan Telegraph Staff Writer (with detailed illustration by Ric Thornton) Although most Macon residents viewed the 1994 flood as an unusual catastrophe, flooding caused by a wandering Ocmulgee River is anything but unusual for Macon. In fact, emergency responders say the city is likely to see similar damage if it rains just as long and hard again. State and federal emergency management funds have paid for ditch improvements and warning systems for Middle Georgia residents threatened by floodwaters. But in recent years, emergency managers have focused on the fact that floods will happen in flood plains, and the most effective way to prevent damage is to move people out of the way. Allowing the river to run its chosen course also offers the advantage of making it a better home for native wildlife and a cleaner source of drinking water, scientists say. Before widespread settlement, the Ocmulgee was a meandering river that constantly carved new channels for itself and spread its floodwaters across large portions of the southern part of Bibb County. Its slow flow made eddies for fish and a stable riverbed for mussels, which helped clean the water. Alligators paddled along Macon's riverbanks. An 1827 map, surveyed shortly after the lands of Bibb County were purchased from the Muscogee (Creek) Indians, shows the Ocmulgee shaped much differently and fringed with a series of lakes made by bends, or oxbows, in the river. The largest was called Lake Superior. An even older riverbed on the west side of modern Macon is still clearly visible from the air. On the 1827 map, it still contains a long, isolated lake called TyeTye. The place where the levee breached in 1994's Tropical Storm Alberto was once a slough where the river still tries to travel when waters are high. Attitudes about flooding have changed in the last decade, said Ken Davis, a public affairs officer for the Georgia Emergency Management Agency. The lion's share of federal and state emergency management grants to Middle Georgia paid to purchase and destroy buildings in the flood plain after Tropical Storm Alberto. "You can elevate things, build structures or dams, but your most effective approach is going to be relocation," he said. The importance of flooding for the environment has also become better understood. In the Western United States, floods are being intentionally created along the Colorado River to scour out the channel and create beds for fish reproduction. The levee's drawbacks Macon's interference in the historic flood plain has had many unforeseen effects, wildlife biologists say. The ecology of the Ocmulgee River has been changed dramatically by the city's efforts to rein in the river - and it's possible that flooding has actually worsened. First, channeling the river by building a levee changed its speed and depth. "You take this complex, meandering channel and turn it into a straight line, and you get a lot more scouring and erosion because of the faster flow," said Brett Albanese, an aquatic zoologist for the Georgia Department of Natural Resources. Before the levee, variable depths, woody debris in the water, and little side channels made great places for a variety of specialized fish to live and breed. "Now the specialists are all gone and you get the generalists - the roaches of the river," Albanese said. Straightening the river also kept it from forming new oxbow lakes, home to larger communities of animals than the river, said Nathan Klaus, a DNR wildlife biologist. The loss of the mussels, which require a stable stream bottom, results in a dirtier river. One square meter of mussels, which once paved parts of the riverbed, can filter 30 gallons of water a day, Albanese said. The Macon levee also reduces the river's access to swamps that help filter impurities from water. The river used to drop its sediment in the flood plain, leaving clay deposits valuable for brickmaking while keeping the river channel from clogging with silt. Regular flooding along the river created a forest peppered with gaps, creating a rich community for birds like bright green, blue and red painted buntings, Klaus said. The levee cut off some parts of the county from this healthy flooding and created "too much of a good thing" elsewhere, Klaus said. "The levee seems to create much more severe flooding across the river from it, so flood events become more intense and catastrophic - more intense than is healthy," he said. This tears down too many trees, creating spaces that have become overrun with privet. Privet is an exotic tree species that crowds out native trees like swamp chestnut oak and sycamore river birch, Klaus said. Native insects don't know how to use privet, and it provides less food for black bears, turkey and deer than the oak acorns once did. To contact S. Heather Duncan, call 744-4225 or e-mail hduncan@macontel.com. |

|

| Unfortunately

-

The Telegraph article below did not consult more

knowledgeable

people such as John Wilson nor the Ocmulgee Sierra

Club. It

merely parrots the Corps of Engineers lack of

visions. |

||

Macon levee in bad shapeCity given deadline for improvementsBy S. Heather DuncanTELEGRAPH STAFF WRITERMacon has the only levee in Georgia that is in such poor condition it might not hold back floodwaters, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers said Thursday. As a result, the corps may revoke the levee's certification, which could drive up flood insurance costs for businesses behind it. For years, the corps has found Macon's levee deficient because of trees and shrubs growing along it, water "boiling" up out of sandy ground behind it, and other structural issues. The 5.5-mile wall of raised earth and concrete divides Macon from the west bank of the Ocmulgee River. Macon officials have continually pleaded a lack of funds to fix the problems. The city is responsible for maintaining the levee, and the corps is responsible for building and inspecting it. Thursday, the corps' national office released a list of 122 inadequate levees, including Macon's, identified during inspections following Hurricane Katrina. That 2005 storm resulted in hundreds of deaths after key New Orleans levees failed. The Savannah district commander met with Macon Mayor Jack Ellis and Bibb County Commission Chairman Charlie Bishop in December, said Billy Birdwell, public relations chief for the Savannah district. "We told them because this was a continual issue, that we were at the verge of decertifying the levee, but we'd hold off for a year if they agreed to make significant movement on fixing it," Birdwell said. Local leaders agreed, Bishop and Birdwell said. Through his spokesman Ron Wildman, Ellis declined to comment. Ken Sheets, Bibb County's engineer, and Bishop said the corps offered to seek funds for a study to pinpoint what modifications the 65-year-old levee needs. They said they don't expect local work on the levee to begin until results are available. Past corps studies have taken years. But Birdwell said regardless of the length or outcome of any study, local governments are still expected to make maintenance improvements during the year, starting now. A Jan. 16 letter from the corps to Ellis indicates that the study would evaluate "the truncation of the Macon Levee in order to minimize its (operation and maintenance) costs." Although in 2004 city officials proposed abandoning more than half the levee - the portion that protects brick yards and a Macon Water Authority sewage treatment plant - that was not specifically discussed in the meeting with the corps, Birdwell and Sheets said. The biggest weakness in the levee is the number of trees and other vegetation that have grown on its banks, Birdwell said. Many of the trees are decades old. Tree roots are believed to weaken the levee by perforating the packed earth, and when trees fall over their roots can pull out large chunks of the bank. But the levee has other problems: Sections of the floodwall are increasingly leaning toward the river; the bank is eroding because of cattle paths; and some water may be seeping beneath it behind Macon Iron. The city has had primary responsibility for the levee since annexing the remainder of it shortly after 1994's Tropical Storm Alberto, which caused flooding throughout Macon when the levee was breached. But county workers maintain the southern portion between the Cherokee Brick and Walker Swamp, Sheets said. If local governments must pay for a portion of the study or for repairs and changes to the levee, Bishop said it's unclear what, if any, obligation Bibb County has. "But we want to make sure we keep Macon and Bibb County in the position of being covered by the federal flood insurance program," he said. Bill Causey, manager of the Macon Engineering Department, has been the levee supervisor for years. But he was appointed this week as interim director of the Public Works Department, and he referred all questions about the levee to Ellis. Sheets noted that many of the large trees have been growing there for years, and corps inspectors never cared until after the 1994 flood. If trees were removed, their root systems would have to be removed and replaced with packed-down fill material, Sheets said. In 2004, Causey said the corps had given up trying to

get the

city

to remove trees from the levee and would instead allow

the levee to be

widened to compensate for the portions perforated with

tree roots. The

city wanted to preserve some of the mature trees, such

as those along

the levee near the John Walker farm, to add beauty to

future expansions

of the Ocmulgee Heritage Trail along the river. To contact writer S. Heather Duncan, call 744-4225 or e-mail hduncan@macontel.com |

||

| Unfortunately,

the

Editors

below

did

not consult with more knowledgeable people before

proposing

some limited options. |

||

| Posted

on

Sun,

Feb. 04, 2007 http://www.macon.com/mld/macon/news/opinion/16610847.htm Levee woes not just a city problemMacon's 5.5 mile long, 65-year-old levee has had a "growing" problem for years, one that should have been corrected but wasn't. Now that problem threatens, in a worst case scenario, to leave the city in danger of flooding. At the very least, the Army Corps of Engineers is threatening to decertify the earthen structure, which would drive up the cost of flood insurance for businesses dependent upon the levee. Army engineers warn that should the Ocmulgee River have a serious flood, the levee might not hold because tree roots over the years have weakened its ability to dam floodwaters. The problem was again broached last December when the head of the Savannah District of the Army Corps of Engineers told city and county officials that the Corps would hold off on decertification if the city and county agreed to make significant improvement on the problem. There are two routes possible in repairing the levee: • Remove the trees and replace their root system with packed-down fill; • Instead of removing trees, widen the levee to compensate for the portions perforated with tree roots. The tree roots aren't the only problem, just the worst. The Telegraph reported that portions of the floodwall are increasingly leaning toward the river; the bank is eroding because of cattle paths; and some water may be seeping beneath it behind Macon Iron. All of these issues must be corrected, and the Corps says it will conduct a study to target needed improvements. However, local governments must proceed with corrections before that study is completed. The question now is how to pay for repairs, and who is liable. The city of Macon annexed all of the levee then outside the city after the flood of 1994, in which a portion of the levee was breached. The city has long said it can't afford to fix the problems, and Mayor C. Jack Ellis has declined to comment on the matter. Bibb County Commission Chairman Charlie Bishop says it's unclear if Bibb County has any financial responsibility. This problem can't go uncorrected. While the levee is in the city, it's also in Bibb County. City voters pay county taxes, too, something Mr. Bishop needs to remember when dividing up the costs |

||

|

| The

BackGround

Color of this page approximates

that of the, quite-often, heavily-silted Ocmulgee River

Floodwaters. The River flows thru Macon-Bibb County, Georgia ... The Ocmulgee has flowed here for well over 100 Millions Years before Man. The Ocmulgee will continue to flow for many millions more years and Nature will survive and thrive whether or not Man destroys his rich farmlands, his fragile built environments and civilizations. |